Grade 91 Steel – How Did We Get Here? Part 1

This blog is the first part of a 3-blog series. To view the rest of the story click HERE for Part 2 and Here for Part 3.

Part 1: History

Thirty years ago, Grade 91 (9Cr-1Mo-V) steel was hailed as the savior of the power generation industry [1]; now it’s behavior has been described as too variable to ensure safe operation [2]. What happened?

At the same time Grade 91 was being developed in the late 1970’s for high temperature nuclear reactor application [3], power plants that had been designed and operated as base-loaded were suddenly cycled on a regular basis. The standard material for high temperature steam outlet headers was first 1¼Cr–½Mo (Grade 11) and later 2¼Cr–1Mo (Grade 22); in both cases headers rapidly began to experience severe cracking in and between header penetrations. The cracking was termed “ligament cracking” [4] and by the mid-1980’s had become a complex reliability crisis without a solution.

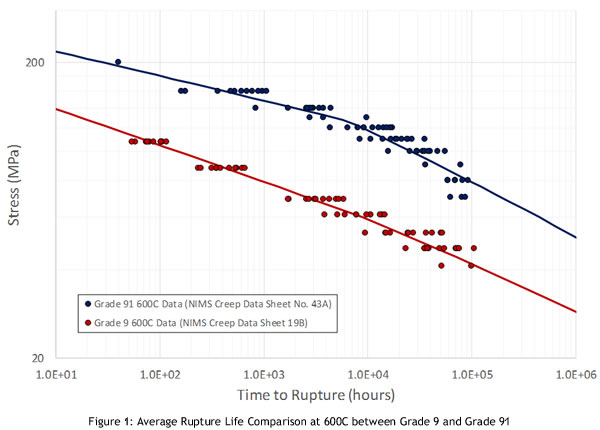

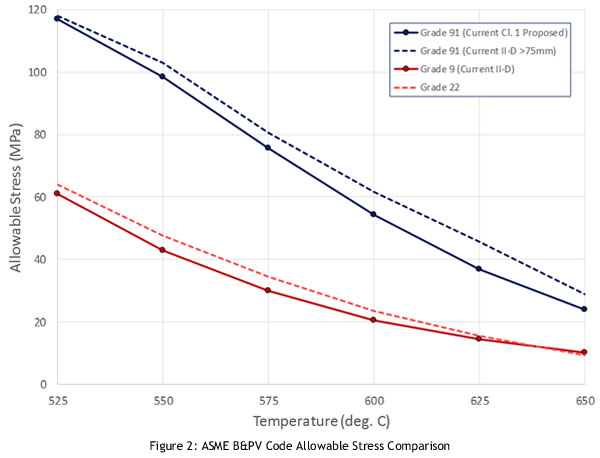

The answer of course was Grade 91. After 10 years of development and exhaustive characterization to support the liquid metal fast breeder reactor project (canceled in 1983), Grade 91 appeared to be exactly what the fossil power industry needed. The material was more oxidation resistant (oxide notching was a significant contributor to the premature ligament cracking in the lower chrome headers [4]) and even had excellent fatigue strength to boot. It was significantly stronger in creep than Grade 11 or 22, so high temperature headers could be made thinner and less susceptible to thermal stress due to cycling. The creep rupture strength at 600°C/1112°F is nearly double that of traditional 9Cr-1Mo (Grade 9) as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. For all these reasons, industry declared in 1990 that Grade 91 “represented a major solution to the ligament cracking problem” with the first header retrofit already planned for that year [1].

The fact that Grade 9 and Grade 91 have nearly identical bulk compositions (i.e. 9Cr-1Mo) but drastically different high temperature strength illustrates that Grade 91 was a new type of material (a “Creep Strength Enhanced Ferritic steel), one that didn’t simply rely on traditional alloying for its performance, but rather a “precise” state of microstructure [5]. The fact that if this precise state of microstructure is not maintained, Grade 91 strength becomes much like Grade 9, has been well-documented over the years [6],[7]. Further, the fact that “normal” fabrication, installation and maintenance practices have been found through repeated premature failures and maintenance struggles to be inadequate [7] – while a continuing source of owner frustration – is not the reason for the most current Grade 91 concerns.

References

- Viswanathan, R., M. Berasi, J. Tanzosh and T. Thaxton, “Ligament Cracking and the use of Modified 9Cr-1Mo Alloy Steel (P91) for Boiler Headers,” Proceedings of the ASME Pressure Vessel & Piping Conference, Volume 201. ASME, New York. 1990.

- Siefert, J. A. and J. D. Parker, “EPRI Data for Grade 91 Steel Linked to Comments on Recommended Code Case,” Presented to the ASME Boiler & Pressure Vessel Code Working Group on Creep Strength Enhanced Ferritic Steels. May 2015

- DiStefano, J. R. et. al., Report ORNL-6303, “Summary of Modified 9Cr-1Mo Steel Development Program: 1975-1985,” Oak Ridge National Lab, Oak Ridge Tennessee. October 1986.

- Nakoneczny, G. J. and C. C. Schultz, “Life Assessment of High Temperature Headers,” Proceedings of the American Power Conference, April 18-20, 1995. Chicago, IL, U.S.A.

- https://www.power-eng.com/articles/print/volume-110/issue-2/features/handling-nine-chrome-steel-in-hrsgs.html

- https://www.epri.com/#/pages/product/1006299/?lang=en

- http://www.ccj-online.com/1q-2005/p91-t91/